Inflation v Growth - Will the RBI blunder?

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is once again confronted with the dilemma of balancing inflation and economic growth. And it is making a mistake.

The Reserve Bank of India (RBI) is once again confronted with the dilemma of balancing inflation and economic growth. However, this dichotomy is misleading. India stands at a critical juncture where poor policy decisions could have far-reaching and detrimental consequences, surpassing the potential benefits of a conservative approach.

Let us understand some key points when it comes to the inflation-growth trade-off.

There are two ways of tackling high inflation

Reduce demand by slowing down the economy by reducing GDP growth OR

Increase capacity to pay - by increasing GDP growth higher.

Hold it! I am not being facetious. Let me explain. There are two types of growth. Rather, there are two types of economic situations in which inflation happens.

One that happens at full employment, which increases wages and puts pressure on prices to rise. This is the wage-price spiral. Economists also call such growth overheating. Here, inflation is caused by high demand, not supply constraints. You reduce inflation by choking this type of growth.

The second situation is when there is no supply. You can see there is unemployment. When growth happens in such a situation, it actually expands the supply, leading to MORE goods, which reduces prices. It also increases employment, improving the affordability of those goods. You stoke inflation by stifling this growth.

India is stuck in the second situation.

We are not at full employment or full capacity. India’s lower employment (below-potential employment) is well known. Our companies, too, are not operating at full capacity. These are clear indications that our growth belongs in the second category.

We were and continue to be a country of shortages. Previously, there were shortages and rationing of consumer goods like radios (yes), TVs, scooters, etc. Today, the shortages are mostly in the agricultural domain.

We are still a supply-constrained economy. In such an economy, reducing growth by raising interest rates worsens inflation. We need more supply, not less. We need more investment, not less. We need more growth, not less.

This food inflation, too, is different.

The present inflation spike has been caused by a lack of supply of vegetables, particularly some specific vegetables like tomatoes, potatoes, onions, etc. However, unlike in the past, the shortage is not perennial but seasonal and episodic.

The vegetables that cause the spike are also important. The food spike has come at a very peculiar time - the time of election in Maharashtra. Maharashtra politicians have been financed by agri-middlemen who control these very vegetable supplies.

This Food inflation can only be fought using fiscal policy, i.e., with free foodgrain support, etc.

Using monetary policy is justified only when there are second-order effects.

Second-order effects refer to higher food prices resulting in demand for higher wages and higher wages resulting in higher prices, hence more inflation.

The recent spike in food prices is not new. Veggie prices have been high for a long time, and despite that, there have been no second-order effects.

As explained above, second-order effects happen in the first type of economic conditions, not in the second type where India is.

But food inflation is stifling growth, right?

Yes, in general, high food inflation does stifle growth.

The most common effect of inflation is reduced consumer spending. This reduced spending slows down the consumption side of GDP and results in lower growth. This is an important aspect of inflation, and we need to understand it better.

When our budget is under pressure, we postpone spending on certain goods (phones, TV, clothes, etc.), which is called discretionary spending, and we cannot postpone spending on others (food, medicines, etc., which is non-discretionary spending).

So, the first demand to collapse is that of discretionary items. This is evident when the prices of these items remain low or even reduced. These prices are captured in non-food inflation, which has declined considerably over the past year.

So what happens after people stop consuming discretionary items and are still facing pressure? Can they consume LESS food or take LESS medicines? The quality of non-discretionary items is compromised but people cannot go without these items no matter what the price, you will try to eat.

But not always - India’s case is different.

India has been giving food assistance to a large part of the population post-COVID. The Modi government’s decision to extend the post-COVID foodgrain assistance for another five years until 2029 makes a lot more sense. Interesting, isn’t it? This will cushion the poor from food inflation shocks.

There are still longer-term shortages in certain food categories. The supply of food and agricultural products—eggs, grains, millet, fruits, berries, fish, etc.- needs to be expanded greatly.

Veggie inflation, specifically, and food inflation in general, can be reduced and controlled through agri-reforms and the development of market mechanisms in the agricultural value chain. [Refer my paper on Smart Agriculture Management System]

Then why is growth anaemic?

The overlooked reasons for below-potential consumption are savings hit after COVID-19. While many commentators have highlighted the GDP impact of COVID-19 in India, not many have done a deep dive. I have some hypotheses about the real impact of COVID-19 that many have missed.

As bad as it was, the impact of COVID-19 was less than it could have been. It was thanks to the resilience of Indian families who had built a savings cushion since our growth got some traction in the 1990s.

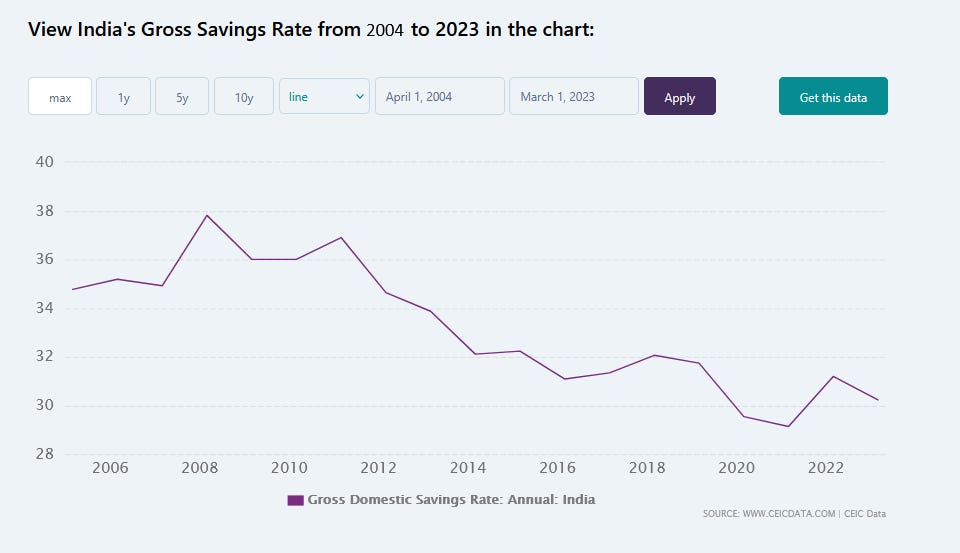

It is critical to note that our Gross savings peaked in 2009 around the Global Financial Crisis. Since then, we have been drawing down our savings thanks to endemic corruption and impairment of the banking system.

If you see the chart, just before COVID-19 struck, Indian savings had perked up slightly.

Indeed, the timing of COVID-19 could not have been worse. It is amazing that we survived this entire event.

In the aftermath of COVID, Indian families will build savings to a comfortable level before the consumption engine fires again. This has nothing to do with veggie inflation specifically.

However, a 6-7% real growth will not be enough.

As a leading economist rightly put it, the present growth rate is far below the aspirational growth rate.

So what is the aspirational growth rate, and how does it compare with what economists usually call the growth potential (or potential growth rate)?

Simply put, the potential growth rate is the maximum achievable growth rate, considering fiscal, monetary, and macro environment limitations.

The aspirational growth rate is what the population expects our economy to perform so that they can improve the quality of their lives. It is a reflection of their dreams.

There is a significant part of this aspiration is created by the social environment.

Thanks to all the infrastructure development, social development and exposure to global benchmarks, India’s aspirational growth rate has touched 12-14% real growth year over year. (If not more).

The potential growth rate remains addled at around 7% real growth you. This is because of bureaucratic bottlenecks and certain reforms that have been made into a political minefield.

In such a backdrop, the actual growth rate of 5.4% or 6% is very underwhelming.

What about Foreign capital and foreign investments?

This fascination with foreign capital and foreign investment comes from a misunderstanding of how money is created. This misunderstanding should have been properly addressed by now since the Bank of England gave an excellent paper explaining how commercial banks CREATE money and thus capital.

India has since 2014 stifled its banks (first by UPA corruption and then by NDA excess conservatism arising from the suit-boot-ki-sarkar scheme).

If we unshackle our banks and investment mechanisms, fast-track our courts (for faster dispute resolution), we will be able to unleash the animal spirits using LOCAL capital.

Regulation has also hamstrung the Indian economy. Where the regulators do not understand or are behind the cutting edge, you see the industry thriving - e.g. IT software, content creation, etc.

This reveals another dichotomy, where FDI and FII investors are treated better, get access to ministers and decision-makers sooner, and are able to protect their capital and assets than local investors. Modi needs to simplify the entire bureaucracy to help Indians profit from Indian growth.

Thus, this has nothing to do with veggie inflation.

Can we first get inflation under control and THEN push growth?

No. Since RBI cannot control this veggie price inflation using monetary policy, it does not mean the RBI should flog the economy into a coma. This is like the “operation is successful, but the patient is dead” scenario.

When you hurt growth, the pathways of economic growth breakdown. It takes a long time to reform them. We have an example before us. If you look at the savings rate chart above, you will note that we have been drawing down on savings since 2008-09. It was only in 2019 that we started to look up. A further choking of the economy may set us back for five, if not ten, more years. We cannot spend a decade with anaemic growth; if the RBI messes up, we will end up spending two decades with anaemic growth.

So it will be a very bad idea for the RBI to sacrifice growth for something it cannot control.

In Sum

The RBI has tied itself up in knots for no reason. There is a clear need to unshackle growth engines and let economic growth ease households' cash flows.

Blind inflation targeting is never a good idea. It is time the RBI woke up.